A version of this article first appeared in the June 2020 edition of our free newsletter, to subscribe click here

One of the aspects of the recent crisis that has been clear to me is the poor risk management ability of our governing bodies.

One aspect of the data regarding the effects of COVID-19 that was consistent from the start was that it manifested the most serious symptoms in older and immune compromised people.

It is clear that most governments either did not understand that or understood it and failed to formulate policies that would be effective in protecting the most vulnerable.

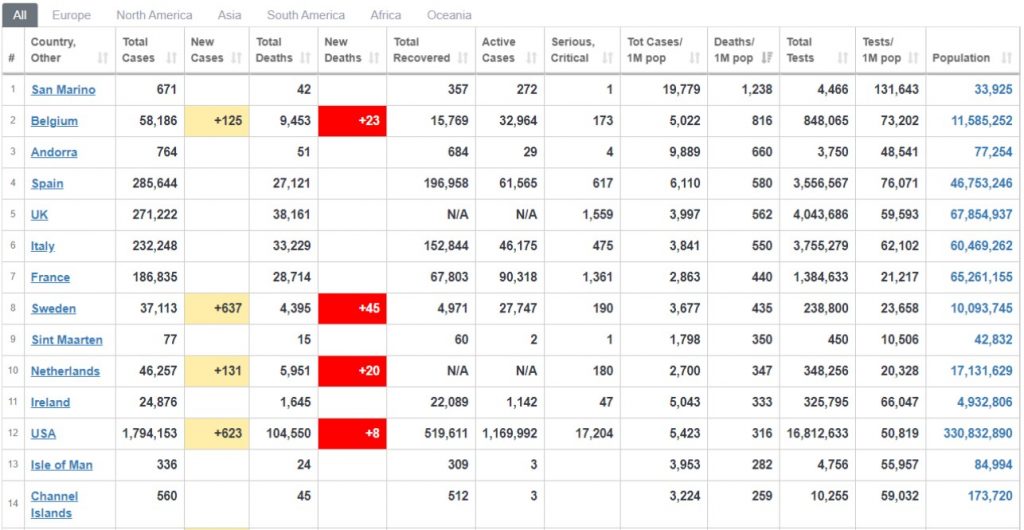

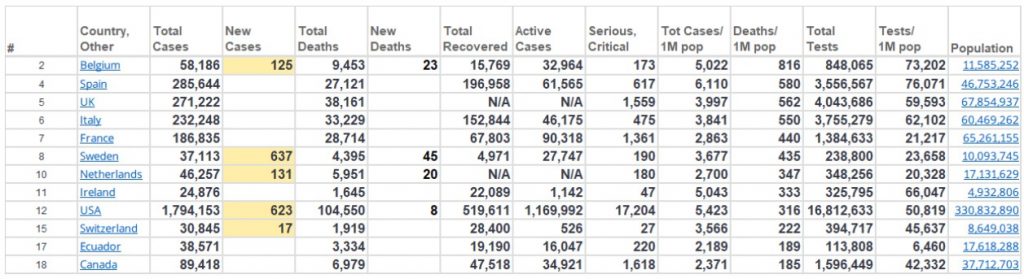

So in order to put that in context let’s examine some figures. One good website for general data is https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Data should come with a warning that all data that you have not collected yourself should be regarded with a degree of skepticism. However, there are consistent trends of data from different data sets from which we can draw conclusions with reasonably high confidence.

I will not be able to show all of the data here but what I am showing is representative of overall trends within the entire data.

And note, within this data the margin of error is never qualified – misreporting, misdiagnosis, false test results, etc. I would recommend to ignore very low percentage values (<1%) as within the likely margin of error of the reporting methodology

Let’s look at some localized data samples

New York City:

(original data source: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-daily-data-summary-deaths-05132020-1.pdf)

The first thing to note is that at any age percentage of total death of people with no confirmed underlying condition is very, very low out of the total sample this is 99 / 15230 = 0.0065 or 0.65%.

Note that this is the percentage of people who have died out of all those who have died from COVID-19, not the risk of death – that is far, far lower.

The number of confirmed cases in NYC on the 13th of may when this data was issued (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_in_New_York_City) = 189509

So out of all diagnosed cases (as of May 13) the risk of death of people confirmed to have no underlying condition was 99 / 189509 = 0.00052 or 0.052%

If you put this in terms of the total population on NYC (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City) = 8336817

So out of the population of NYC (as of May 13) the risk of death of people confirmed to have no underlying condition was 99 / 8336817 = 0.000012 or 0.0012%

To put this in context in NYC in 2019 there were 218 traffic fatalities (Source: https://abc7ny.com/traffic-fatalities-deaths-new-york-city/5802477/)

Twice as many as those confirmed not to have pre-existing conditions have died from COVID-19 than died in traffic accidents in NYC.

If you are healthy you face a greater risk when driving a car, riding a bike or crossing the road.

If we make the assumption that the NYC data is representative (I have reviewed other data sets and this data is generally similar to other reported data), what conclusions can we generally draw about how the virus affects the general population?

- If you are ‘healthy’, regardless of your age, the illness appears to present no statistically significant elevated threat of death

- If you are ‘not healthy’ regardless of your age the illness appears to present a statistically significant elevated threat of death.

In the context of these conclusions, does the strategy for mitigation of the effects of the virus adopted by most governments make sense?

To me, the answer to that question is easy. No.

We can see this by comparing the results of the different strategies from different governments

Comparing deaths per 1M of population (Source: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/)

I took this data, brought it into Excel and removed all countries with populations less than 1M people. You can see from the data that countries with small populations are overrepresented in the deaths per capita data. I regard these as statistical anomalies and have removed them. That phenomena is worthy of a closer look but that is not the purpose of this article.

With those countries removed the data looks like this:

Of these countries (with the exception of Ecuador, I have not examined the public policy at the time of writing) Sweden has not implemented significant restrictions on freedom to combat the spread of the virus. The rest of the countries in this group have implemented strict ‘lockdown’ policies. Sweden has adopted some mild mandatory restrictions but made most of the measures to combat the spread of the virus voluntary.

What can we conclude from this?

From this one data point it appears there is no benefit to be gained between a strict, police enforced lockdown lasting for months and a voluntary social code of conduct.

If we take a step back, what ‘meta-lesson’ can we learn from this?

- The perception of risk is more important than the actual risk

- In formulating public policy the perception of risk is more important than data

This is an aspect of human nature called the precautionary principle. In the past, individuals used to be left to make their own precautionary and preventive risk decisions.

In recent years, governments have assumed the right to do this. Initially some good came out of this – traffic laws, vaccinations, etc.

If we examine public policy further we can also see something important, which is this:

The direct negative consequence of a precautionary public policy is ignored, and almost never reported, as long as the negative consequence is less than the most dramatic perceived risk.

It is also very hard to gather data on the negative consequence of government policy. It is not in the government’s interest to gather data on the failures of the policies they implement.

So how is this relevant to aircraft development?

I am working with a European EVTOL developer and we have spent some time going through the EASA special conditions for EVTOL aircraft.

There was a small change to the established regulations that caught my attention. (Source: https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/SC-VTOL-01.pdf)

Can you spot it?

This is the same regulation in the new part 23 regulations:

And the equivalent from part 25:

The word ‘or’ has been inserted between the words detrimental and permanent.

Previously when qualifying aircraft structure, deformation had to be both permanent and detrimental to be disallowed. Now either detrimental deformations or permanent deformations are disallowed.

This raises two critical issues:

1: How do I show that any deformation is non detrimental? Any deformation could be associated with an eventual reduction in strength and therefore safety.

2: For metal structure there are many small scale, permanent, non detrimental deformations that occur at limit loads caused by local KT effects taking the metallic materials above the proportional limit. This rewording of the regulations implies that I have to take account of KT effects at limit level loads in static analysis of metallic structures.

If this new wording of the regulations is to stand, what effect will this have on the certification process for the applicant and what effect will it have on the aircraft product?

The results are relatively easy to predict.

Because this is a new requirement, it introduces uncertainty into the process. Uncertainty invariable creates delay and cost. The extent of the delay and additional cost is unknown. We can only hope that it will not be significant.

The only mitigation for this new standard is additional stiffness and a means to reduce stresses. This means additional weight.

There is no doubt that this new approach will increase safety. However, most changes to the regulations are initiated by a failure in service that informs a means to prevent that failure occurring again.

I know of no failure in service of a structure that complies with 23.2235, 23.305 or 25.305, and has been caused by an insufficient measure of safety inherent in the wording of that regulation.

A government employee has arbitrarily and unjustifiably applied the precautionary principle to a new set of aircraft regulations.

This change will increase cost and program time and will result in an aircraft product with lower performance. For an intangible, unnecessary and unquantifiable safety benefit.

Is the future for the industry a set of ever decreasing circles of unnecessary regulatory constraint and the resulting cost and performance negatives?

As with most safety issues the problems occur not because of a lack of appropriate standards in the written regulations. They occur because the regulatory process is circumvented or because of simple human error in the application of the existing standards.

Unless we analyse the shortcomings of the adoption of the precautionary principle at a governmental level, are we doomed to apply it at ever increasing levels?

What do you think? Has the government’s response to COVID-19 been good or bad? What have we learnt and how can we do things better in the future?

Are we creating a culture of mandating higher and higher levels of safety? What does this mean to the aircraft industry?

Richard. Good read! Don Joseph

I hope you are not a pilot. Your cavalier acceptance of risks will have me checking maintenance logs carefully to ensure nothing I fly has any relation to your company.

Over one million deaths due to COVID, and you trivialize it as a mere perception problem. Like permanent deformation in a structure. What’s the excitement over a little permanent deformation?

I suppose that the logical extension would be that as long as the cracks in a structural component do not interfere with the safe operation of an aircraft, why worry? It’s just a perception problem.

The regulations are there to protect the public from corner cutters, who are simply frustrated their design skills are insufficient to adhere to the regulations. Every failure of design, or materials in aviation has a cost. The regulations are a result of lessons learned, and in many cases, the cost was human lives.

You Sir, show a profound lack of respect for the value of human life. If you have no concern for your own, that is your business. However, when you advocate the removal of regulations, and cherry pick data, and use convenience as an excuse to erode safety, you join the ranks of those “engineers” who are more gambler than scientist, using others lives as your chips.

I have never heard of Abbott Aerospace before, and hope I never again will.

The article was about perception of risk but it is also about actual calculated risks.

Your point here is worth examining further:

I suppose that the logical extension would be that as long as the cracks in a structural component do not interfere with the safe operation of an aircraft, why worry? It’s just a perception problem.

You are clearly not aware that all metallic commercial aircraft flying around over a certain age are full of hundreds or thousands of cracks, all of which are monitored and inspected to make sure they keep within critical limits. There are many articles you can read on this if you are interested.

Rational real life risk assessment and calculations are what aircraft engineers do. Nothing is ever 100% safe, we live in a world of carefully managed risks – and those risks are all calculated and managed for you by engineers working to government regulations.

I live in Canada and on average one person a day is killed by falling down a flight of stairs. But we do not mandate the use of single storey buildings. For all governments (and societies) there is an acceptable risk of death for all sorts of products and activities. You may not be aware of this but this is the way the world around you is created.

In aircraft design the regulations and safety standards are wholly constructed around the acceptable risk of catastrophic (fatal) events. When you next fly on any aircraft you should keep this in mind. For transport category aircraft by design the aircraft can only ensure your safety at the minimum level of a 10^7 risk.

This is the world all engineers work within – and we all live within.

There is a difference between actual risk (arrived at by data analysis) and perception of risk (quick – outlaw all staircases!). If we base public policy on a misleading perception of risk our society would look very different. There might be no aircraft at all – or cars, restaurants, electrical appliances, etc

Feel free to continue the conversation, you seemed to read some intent into the article that was not intended.